McConnell is not omnipotent

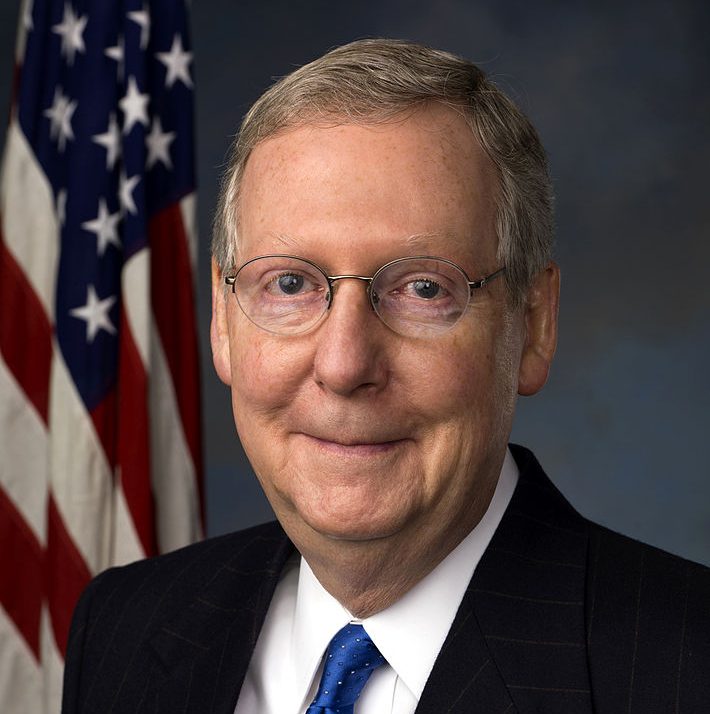

This week, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., suggested that he alone has the power to select the measures on which his colleagues vote. When McConnell was asked why the Senate was not likely to vote on a House campaign finance proposal (HR 1), he replied, “Because I get to decide what we vote on.”

Such assertions are not new for McConnell. For example, he declared just last year that the Senate would not vote on legislation to protect special counsel Robert Mueller, even if it was approved by the Judiciary Committee. His promise at the time was unequivocal. “I’m the one who decides what we take to the floor, that’s my responsibility as the majority leader, and we will not be having this on the floor of the Senate.”

Yet the Kentuckian does not have that kind of power. He is not omnipotent. Being majority leader does not allow him to prevent senators from trying to pick the measures on which they votes. While leaders have indeed assumed a more significant role in managing the legislative process in recent decades, they have been empowered to do so every step up of the way by the voluntary deference (or sufferance) of rank-and-file senators. McConnell’s assertions should, therefore, be qualified. He gets to decide what the Senate votes on, but only so long as his colleagues let him make that decision.

Setting Priorities

All legislative bodies need a mechanism that enables their members to determine which measures get votes and which ones do not. In the Senate, that mechanism is the motion to proceed (or unanimous consent). A simple majority of the Senate must first vote to proceed to a measure (or all senators must consent to proceed) before a formal debate can begin. Senate Rule VIII stipulates that motions to proceed to are debatable (i.e., senators can filibuster them) in most circumstances. A three-fifths majority of the Senate (usually 60) must, therefore, vote to invoke cloture (i.e., end debate) on the motion over the objection of any senators who are able and willing to continue speaking. This means that either a simple majority or a super-majority of senators, not just McConnell, is needed to select the measures on which the Senate votes.

Making motions

Of course, a senator could still get to decide the issues on which the Senate votes if he or she is the only member who gets to make a motion to proceed. This is the message implied in McConnell’s confident assertions. They give people the impression that only the majority leader gets to move to proceed to a measure under the Senate’s rules. However, the Senate’s rules make no distinctions between senators when it comes to the motion to proceed. Rank-and-file senators merely defer to the majority leader to make such motions because it makes their professional lives more comfortable. They can just as easily chose not to defer if they are unsatisfied with how McConnell is managing the Senate in a specific situation. That’s what happened in 2010 when McConnell, then the minority leader, made a motion to proceed over the objections of Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-NV.

| Topics: | Representation & Leadership |