What happens when the House picks a Speaker?

In the wake of the federal elections last week, all eyes immediately turned toward the Democratic Party and the impending transfer of power in the House of Representatives. While many observers are looking forward to January and analyzing what is likely to happen in DC with a Democratic House, many of the most consequential decisions for the 116th Congress are being made now, as the parties hold their organizing meetings in preparation for the new Congress.

Having captured a majority of seats in the House, the Democrats will assume institutional control of the chamber; key political decisions that flow from this control will be made in Democratic caucus meetings happening this week and after Thanksgiving. These decisions include: proposing and ratifying changes to party rules and drafting the Rules of the House for the 116thCongress, electing chairs of all of the committees, making rank-and-file committee assignment nominations, and selecting party leaders.

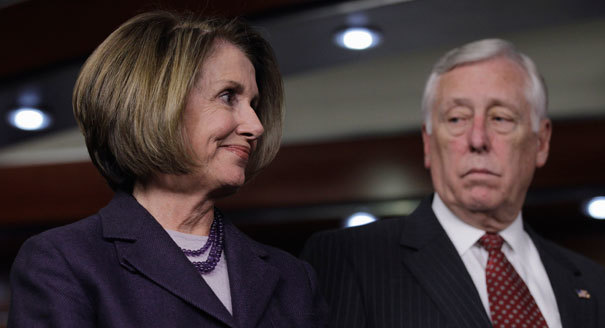

The most important preliminary decision for the House is the selection of the Speaker. Current minority leader Nancy Pelosi is seeking to return to the Speakership, a position she held for four years (2007-2010) when the Democrats were last in control of the House of Representatives. While she is a favorite to return to the top spot in the House and has wide support among House Democrats, a small group of anti-Pelosi Democrats is challenging her bid for the Speakership. While no actual alternative candidate has emerged to make a bid for the office, the procedures used to pick the Speaker create, in theory, significant leverage for the anti-Pelosi faction.

Procedurally, choosing a Speaker is relatively straightforward: on the first day of a new Congress, the Clerk of the House presides over the chamber, and an election for Speaker is held as the first order of business; nominations are made for candidates, and then a roll-call vote is taken. Under longstanding practice, members are called in alphabetical order and vote for candidates by voice; to win, a candidate needs to receive a majority of votes cast by Members “for a person by name.” If no candidate receives the requisite majority, the roll call is repeated. Several times in American history—notably in 1849 and 1859—it took numerous votes over the course of many weeks to elect a Speaker.

The key structural feature of the Speaker election is that it is the only leadership office that is elected by the entire membership of the House. All other leadership positions—majority and minority leader, party whips, and lesser offices such as caucus chair—are selected privately by the parties in caucus elections. Both parties also hold private elections for the speakership, but only to choose nominees. Ultimately, those nominees must stand for election on the House floor. Consequently, a member seeking the speakership need only garner the support of a majority of their caucus to gain the nomination (roughly 115-120 votes in the new Democratic caucus, post-election), but need to secure a majority of the House (218 votes if everyone participates) to win the Speakership.

Traditionally, a norm has existed in both parties that all members support their party nominee when the vote goes to the House floor. That is, even if the vote in the caucus is 130-110, the 110 who did not vote for the nominee are expected to back them on the House floor. From 1947 until 1997, there was not a single defection from this norm. In recent years, however, a small number of members of both parties have defected from their party nominee. In 2011, 18 votes went to candidates other than the party nominees. In 2013, 14 votes did. In 2015, 28 did. In 2017, 5 did. In none of these cases did the votes comprise the balance of power such that they could deny the election to the majority party’s candidate. In several of the elections, however, a faction of conservative Republicans explicitly sought to use the floor vote to deny their party’s nominee the Speakership.

This is the dilemma currently facing Minority Leader Pelosi. She has wide support in the Democratic caucus—she will easily win the nomination vote—and no individual challenger who wants to run against her for the nomination. A small group of about 20 conservative-leaning Democrats, however, are pledging to not vote for her on the floor. If they are not bluffing, Pelosi would not have 218 Democratic votes to secure the Speakership. Earlier this week, 17 of these insurgents signed a letter, perhaps further committing them to their position. Similarly, nine Democrats associated with the Problem Solvers caucus in the House are vowing to withhold their vote for Pelosi unless she agrees to certain changes to the House rules.

So what happens next? A lot depends on the motivations of the insurgents and the strategic choices of Pelosi. The caucus nominating vote is not scheduled until after Thanksgiving, which gives both Pelosi and the insurgents a chance to bargain. Perhaps the insurgents are looking to be “bought up” and will settle for winning some changes to the House rules or party rules, or some consideration regarding committee assignments, campaign funding help, or other goodies. Pelosi does not need to satisfy all of the insurgents; if she can buy up half of them, she will be able to secure an easy majority on the floor.

Many observers believe that a commitment by Pelosi or other current leaders to step down in the near future might satisfy the insurgents; the current top Democratic leadership has been in place for 16 years, and there is definitely some general caucus dissatisfaction related to the inability of members to move up the leadership ladder. Alternatively, Pelosi might threaten to punish members who vote against her on the floor; rule 34 of the Democratic caucus binds members to vote for the nominee. When two members of the GOP leadership voted against Speaker Boehner in 2015, he immediately removed them from the Rules Committee.

If bargaining fails, Pelosi could call the insurgents’ bluff, and simply win the nomination in the caucus and go to the floor with it, daring them to deny her the Speakership. Similarly, she could lean on some of them to vote “present” on the floor, rather than for a different candidate. Under current House rules, nominees need a majority of those voting “for a person by name” to win the Speakership. If anyone votes “present,” the total number of votes is reduced by 1, meaning that for every 2 people who vote “present,” the threshold needed to win reduces by 1 vote. If Pelosi could convince 10 Democrat insurgents to vote “present,” she would only need 213 votes, which would neutralize the balance of power held by the holdout insurgents.

Tactically, Pelosi could also employ the help of Republicans, though relying on them to sustain her Speakership would be a dangerous (and highly unlikely) move. Republicans could outright vote for her for Speaker to make her majority, or they could vote “present” to reduce the majority threshold. They could also vote in favor of a resolution declaring that the Speakership be decided on a plurality basis; this broke the Speakership deadlocks in both 1849 and 1856. But again, all of these possibilities are highly unlikely.

The insurgents could try some tactical maneuvers as well. For instance, the party rules regarding Speaker nomination are not fixed; the majority of the caucus could vote to require a potential nominee to secure 218 votes in the caucus to win the party nomination. Successfully securing such a change would gain the insurgents the ability to block Pelosi without having actually to vote against the Democratic nominee on the floor. Even securing a strong showing in a loss on such a rules change vote might topple Pelosi politically. Given the overwhelming current strength of Pelosi within the caucus, however, this seems exceedingly unlikely to occur.

This post originally appeared in Legislative Procedure on November 16, 2018.

| Topics: | Representation & Leadership |